In early August, the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) released a draft 2.0 version of its landmark Cybersecurity Framework, first published in 2014. A lot has changed over the past 10 years, not least of which is the rising level of cybersecurity threats that the original document set out to help critical infrastructure defend against.

While meant to help reduce cybersecurity risk to critical infrastructure the CSF saw wide adoption by both private and public sector entities. Relying solely on voluntary adherence to the CSF has proven inadequate in establishing sufficient cybersecurity measures for critical infrastructure. The ransomware attack on Colonial Pipeline in 2021 was a glaring evidence of that. Consequently, the Biden administration responded by instituting obligatory cybersecurity standards within critical infrastructure sectors such as oil and gas pipelines, rail, aviation, and water.

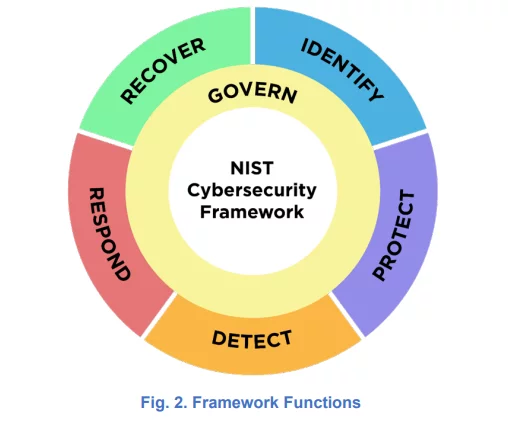

CSF 2.0 broadens the CSF’s reach to all software producers of any size, technological stack, and sector, stresses cybersecurity governance, and emphasizes cyber supply chain risk management. Additionally, the new framework adds one more pillar to the original five needed for a successful cybersecurity program. The original five were: Identify, protect, detect, respond, and recover. CSF 2.0 introduces a sixth: Govern.

In this article, we’ll try to summarize the new additions to the framework and see how the framework could help you in starting or advancing your existing cybersecurity risk management program. It’s important to note that this new version is not yet final. The draft is open for comments until early November and is scheduled to be released in early 2024. That means that if you have any comments or additions you’d like to see added you still have time to offer them to NIST for consideration.

Main Changes In CSF 2.0

The CSF 2.0 draft keeps the essential aspects of the original framework. CSF 2.0 is voluntary for the private sector; it takes a risk-based approach to cybersecurity (focusing on the cybersecurity outcomes that organizations seek rather than the specific controls that must be implemented); and it retains the CSF’s essential structure, which consists of three main components:

- Pillars – The heart of the CSF integrates intended cybersecurity outcomes into five “functions” or pillars: identify, protect, detect, respond, and recover. (CSF 2.0 introduces a sixth: Govern.) These functions are the needed components of effective cybersecurity. Around the main 5 pillars, the original CSF includes 23 categories and 108 subcategories of intended cybersecurity results, as well as hundreds of helpful references, largely other frameworks and industry standards, clustered around them. The version 2.0 draft is even more extensive.

Source: CSF 2.0

- Framework Tiers – The CSF tiers define how a company manages cybersecurity risk. Organizations select the tier that best fulfills their objectives, decreases cyber risk to an acceptable degree, and is easily implemented. The tiers offered progress from 1 to 4 (‘Partial’ to ‘Adaptive’) and demonstrate an increasing level of sophistication.

- Framework Profiles – The CSF profiles assist companies in finding a path that’s right for them to reduce cybersecurity risk. They define an organization’s “current” and “target” cybersecurity postures and assist them in transitioning from one to the other.

The CSF 2.0 draft incorporates the following key changes:

- Scope – The new framework is intended for use by organizations of all sizes and industries, including SMBs. This move reflects the fact that in 2018 Congress explicitly asked NIST to address small business concerns in connection with the original framework. Revising the document’s language to remove references to critical infrastructure and replace them to include all organizations reflect the framework’s expanded scope.

- The Governance pillar – CSF 2.0 expands on the CSF’s risk-based cybersecurity methodology. CSF 2.0 acknowledges that dramatic changes over the last decade have elevated cybersecurity to a key source of enterprise risk (including company interruption, data breaches, and financial losses). To address these changes, CSF 2.0 enhances the relevance of governance and places cyber risk at the same level as legal, financial, and other forms of enterprise risk for senior leadership. The new governance function addresses how an organization makes decisions to support its cybersecurity strategy, and it is designed to inform and support the other five functions.

- Supply chain risk management – The efforts required to control cybersecurity risk connected with external parties are referred to as supply chain risk management (SCRM). Supply chains expose a firm to cyber risk. Malware assaults (for example, the 3CX trojan attack), ransomware attacks, data breaches (for example, the Equifax data breach), and cybersecurity breaches are all common supply chain cyber hazards.

Third-party tools and code see increasing uses in almost all aspects of software production and so we see a corresponding rise in software supply chain risks. Any third party with access to an organization’s system, including data management companies, law firms, email providers, web hosting companies, subsidiaries, vendors, subcontractors, and any externally sourced software or hardware used in the organization’s system, can launch supply chain attacks. Tampering, theft, unauthorized introduction of code or components into software or hardware, and poor manufacturing procedures are all software supply chain hazards. Organizations that do not manage software supply chain risks adequately are more likely to suffer such an attack.

CSF 2.0 adds more information on third-party risk, incorporating software supply chain guidelines into the new governance function, and specifies that cybersecurity risk in software supply chains should be taken into account while an organization performs all framework functions (not just governance). The new SCRM language is one of the changes. CSF 2.0 lists the following as desirable SCRM outcomes:

- Suppliers should be “known and prioritized by criticality” (GV.SC-04)

- “Planning and due diligence are performed to reduce risks before entering into formal supplier or other third-party relationships” (GV.SC-06)

- “Supply chain security practices are integrated into cybersecurity and enterprise risk management programs, and their performance is monitored throughout the technology product and service life cycle.” (GV.SC-09)

The draft also invites companies to use the CSF’s Framework Profiles “to delineate cybersecurity standards and practices to incorporate into contracts with suppliers and to provide a common language to communicate those requirements to suppliers.” According to NIST, suppliers can utilize Framework Profiles (see above) to communicate their cybersecurity posture as well as relevant standards and policies concerning software supply chain risks.

- Cloud security – The original CSF addressed cloud security, but only in circumstances where an enterprise maintained and guarded its own cloud infrastructure. This use case is no longer the most common. Organizations are rapidly transitioning to cloud settings in which third-party corporations manage the cloud legally and operationally. (For example, administration of the underlying infrastructure is outsourced in platform-as-a-service and software-as-a-service cloud computing models.)

Through its improved governance and supply chain risk management provisions, CSF 2.0 enables enterprises to better use the framework to build shared responsibility models with cloud service providers, and it facilitates some degree of control in cloud-hosted settings.

- Expanded implementation guidance – To assist companies in achieving the cybersecurity outcomes outlined in the framework, CSF 2.0 provides additional “implementation examples” and “informative references.” While these resources are considered part of the framework, NIST will keep them separate to allow for more regular upgrades.

Implementation examples provide more information on how to put the framework into action. They do not describe all actions that could be taken to accomplish a specific objective, rather, they are “action-oriented examples” intended to assist businesses in understanding “core” results and the first activities that may be taken to attain such outcomes.

Using the CSF 2.0

The CSF, like NIST’s other frameworks, is very light on exact details on how to implement its suggestions. There is no full or partial checklist you can utilize as a first step in setting up or expanding your organization’s cybersecurity risk management. Having gone over the extensive list of ‘desired outcomes’ the framework still leaves the burden of implementation on the individual companies. The logic is that with each company being unique in its tech stack, its existing threats, and risks, there is no easy or comprehensive way to tailor a ‘one list suits all’ cyber threat solution framework.

Still, the framework is not without its uses. For one thing, the Profiles and Tiers offered in the framework offer a good way to at least start planning where the company’s cybersecurity response plan and risk management ought to be. It gives the company’s management a clear indication that cyber risks should be considered on par with any other major risk category (like legal or financial) which should, in theory, help the CISO get the funding and manpower they require to handle the risks they have mapped for their organization. Lastly, having a newly added section concerned with SCRM shows how seriously companies should consider the various threats that are inherent in a potential software supply chain attack or breach.

The fact that NIST intends to offer a more robust and frequently updated implementation guide that includes examples is a step in the right direction. It remains to be seen how extensive and helpful it really is. There is still a good chance you won’t be able to ingest and apply this old/new framework without at least one person knowledgeable in cybersecurity.

At least regarding the software supply chain risk part, Scribe’s platform get you covered. Scribe has a free tier where you can start trying it now with all of our extensive capabilities at your fingertips to play with. This includes starting to generate and store SLSA provenance and fine-grained SBOMs for your builds. If you are interested in Scribe’s ability to offer you custom-made user policy to govern your SDLC process, I invite you to check out this article.

Either way, I encourage you to give our platform a try and examine the usefulness of the security information Scribe can offer as it is accumulated and analyzed over time.

This content is brought to you by Scribe Security, a leading end-to-end software supply chain security solution provider – delivering state-of-the-art security to code artifacts and code development and delivery processes throughout the software supply chains. Learn more.